Medieval Punishment

When talking about the Medieval punishment, we must first speak of torture, which might be either previous or preparatory; previous, when it consisted of a torture which the condemned had to endure previous to the capital punishment; and preparatory, when it was applied in order to elicit from the culprit the acknowledgement of his crime or of his accomplices. It was also called ordinary, or extraordinary, according to the duration and the violence of the means to inflict it. In some cases, the torture lasted five or six hours, in others it rarely exceeded one hour.

The Medieval punishment by torture included the compression of the limbs by special instruments, or by ropes only; injection of water, vinegar, or oil, into the body of the accused; application of hot pitch, and starvation were the processes most in use. Other means were placing hot eggs under armpits, tying lighted candles to the fingers, so that they might be consumed simultaneously with the wax, letting water trickle drop by drop from a great height on the stomach, or watering the feet with salt water and allowing goats to lick them.

The Pillory In Central Paris

In France, the torture varied according to the provinces, or rather according to the parliaments. In Brittany, the culprit, tied in an iron chair, was gradually brought near a blazing furnace. In Normandy, one thumb was squeezed in a screw in the ordinary, and both thumbs in the extraordinary torture. At Orléans, for the ordinary torture, the accused was stripped half naked, and his hands were tightly tied behind his back, with a ring fixed between them. Then, by means of a rope fastened to the ring, they raised the man, who had a weight of one hundred and eighty pounds attached to his feet, a certain height from the ground. At Avignon, the ordinary torture consisted in hanging the accused by the wrists, with a heavy iron ball at each foot.

After the torture, the next step in the Medieval punishment was the execution. The person carrying the task, the executioner, did not hold the same position in all countries. For certain areas in France, Italy and Spain, a certain amount of opprobrium was attached to his terrible craft. In Germany, on the contrary, successfully carrying out a certain number of capital sentences was rewarded by titles and the privileges of nobility.

In France, the executioner was generally forbidden to live within the precincts of the city, unless it was on the grounds where the pillory was situated. In some cases, so that he might not be mistaken amongst the people, he was forced to wear a particular coat, either of red or yellow.

On the other hand, the role this sinister personage held in the last stage of Medieval punishment ensured him certain privileges. In Paris, he possessed the right to take all he could hold in his hand from every load of grain which was brought into the market. However, in order that the grain might be preserved from the ignominious contact, he levied his tax with a wooden spoon. And, beside the personal property of the condemned, he received the rents from the shops and stalls surrounding the pillory, in which the retail fish trade was carried on. In consequence of the receipts from these various duties forming a considerable source of revenue, the prestige of wealth by degrees dissipated the unfavorable impression traditionally attached to the duties of executioner.

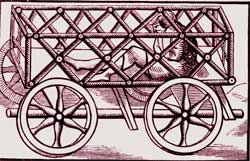

The Iron Cage

The popular belief also ascribed to the executioner a certain practical knowledge of medicine, which was supposed inherent in the profession itself, and the acquaintance with certain methods of cure unknown to doctors. More than once during the 13th Century the duties of the executioner were performed by women, but only in those cases in which their own sex was concerned.

There were different ways of carrying out the final stage of the Medieval punishment. The punishment by fire was always inflicted in cases of heresy or blasphemy. The Spanish Inquisition made a constant use of it. In France, in the beginning of the 14th Century, fifty-nine Templars were burned at the same time for the crimes of heresy and witchcraft. And three years later, on the 18th of March 1314, Jacques de Molay, the Great Master of the Order of the Templars, also perished in the flames on the Island of Notre Dame. Joan of Arc was condemned to death by fire as a witch and a heretic.

Decapitation was another mode to carry out the death sentences. In some countries, it was performed with an axe, or, as in France, with a two-handed sword. The victim was allowed to choose whether he would have his eyes covered up or not.

One of the most horrible methods of Medieval punishment was the quartering, performed using ropes attached to each of the limbs of the condemned. The ropes were fastened to four bars, to each of which a strong horse was harnessed.

Overall, hanging was the most used method of execution in France. In every town, and almost in every village, there was a permanent gibbet.

When it was only necessary to stamp a culprit with infamy, the Medieval punishment consisted in the penalty of the lash and the pillory. The pillory was a sort of a scaffold bearing on its front the arms of the feudal lord. In Paris, it was actually a tower, built in the centre of the market. It had a horizontal wheel with holes, made so they hold the head and hands of the culprit, who, on passing before the eyes of the crowd, came in full view, and was subjected to their hooting.