Medieval Music

The Medieval Music evolved slower than any other art, however, with the impulse of Christianity, she burst into immortal epic and songs of hope and love. The development of music during the first ten centuries of Christianity was intimately associated with the Church.

Medieval religious music

In the second century appeared the conception of a universal Church, and such a conception naturally widened and strengthened the influence of the music. An attempt was then made to establish a common hymnology for Christendom. The building of magnificent churches led to the appointment of choirs specifically trained to perform during the religious services.

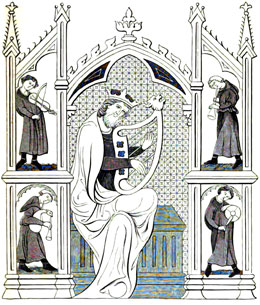

King David Playing the Lyre

13th Century

St. Sylvester established a music school in Rome, and in the later years of the fourth century original hymns were introduced, based on poetry independent of all tradition. Through their influence, SS. Chrysostom and Cyprian contributed to the admission of new melodies into the religious service, but it was reserved for St. Ambrose to establish for two centuries the future form of Church music.

Gregory the Great did the most to enlarge and establish the Medieval musical art. At the end of the sixth century he ascended the chair of Papacy, and he promoted a canonical method of musical service designed to provide satisfaction to the people, and, in the same time, to ensure harmony of spirit and unify the component parts of Christendom. He instituted what was called after his name the monophonic Gregorian chant. Charlemagne facilitated the adoption of the Gregorian music method by founding singing schools in various cities of the empire. Under his reign, the instrumental music was also greatly encouraged.

The organ, known from antiquity and perfected by the Byzantines, will become the main instrument used in the religious service. First it found its way into Germany, and from here it was imported in Italy, and subsequently into England and France, for the same purpose, to be used in Divine service.

Medieval polyphonic music

The polyphonic music of the Middle Ages was the ancestor of the modern techniques of composition developed starting with the sixteenth century. The ritual plainsong was the foundation of the education of the medieval musician, and the basis of his qualifications.

The polyphony can be understood only in relationship with the order and forms of the liturgy, as is the case with the liturgical arts of poetry, music, and ceremonial. The liturgy had a devotional function and a didactic purpose which resembled and complemented those of the buildings in which was held. We refer here to the Gothic cathedral, which was an encyclopedia carved in stone, and as such, the yearly cycle of the liturgy was a visual and musical representation of Christian doctrine and history.

Medieval composers and singers

The medieval composer and the musician did not perform to the public as private individuals. They were always members of an organized community which had a wider purpose than a purely musical one, and which had its rules applied not only on their musical activities but also on their daily lives.

If the composer was a member of a monastic community, the rule and duties of the order applied to him as to any of its other members, and the musical traditions and customs of his community determined the scope of his creative work. The singers in a Medieval cathedral had duties concerned only with the observance of the ritual music and its plainsong. As a result, they had greater opportunities than the members of a monastic community to develop their musical talents and to contribute to the elaboration of the liturgical music.

The patronage of some Bishops and higher clergy helped to improve the organization and musical standards of the cathedral choirs, and enabled them to play an important part in the development of polyphony in the later Middle Ages. The leading role in the advance of Medieval music belonged to the more recent collegiate churches, colleges and private household chapels.

In many of these newer medieval institutions the singing of polyphonic music was a daily observance. Consequently the composition and balance of their choirs were more elaborate, the qualifications of their singers were more exacting, provision was made for training their boy choristers in polyphony, and the demands on their composers increased significantly.

With these new foundations came changes in the social position of musicians. This is especially true of household chapels, where the singers ranked in the household organization as 'gentlemen', and were no longer required to be in the lower orders, as were singers in most of the collegiate churches and colleges.

In the later Middle Ages, the monasteries contributed to the increase in the number of lay singers. Many of the larger abbeys supported choirs of laymen and boys who were put under the charge of a lay cantor. Thus the choral foundations participating in the cultivation of Medieval polyphonic music had a very diverse character: secular and monastic, cathedral and collegiate, royal and aristocratic, educational and charitable.

Medieval secular music

The Church was exercising a powerful influence over certain forms of musical art. In the same time, the ordinary people, without refusing the more serious perceptions embodied in sacred songs, wanted to also hear music inspired by natural emotion, and supplying a mood of brightness, freedom, and grace. Membership in a secular community brought demands and opportunities of a different kind.

Charlemagne himself collected the heroic songs and sagas of the Germans. Later on, folk songs were carried from province to province, from country to country, by the wandering minstrels, a class to whom the protection of the law and the sympathy of the Church were, in their beginning, denied. The musicians promoting the secular Medieval music were the English minstrels, the Spanish trobadores, the troubadours in France, and in Germany the minnesingers.

Medieval Royalty listened to music performed by the courtly musicians, who abandoned the old Church models and started to use the modern major and minor keys. The preferred compositions were the canzonets, servantes, tenzone, roundelays, and pastourelles.

In Germany, the minnesingers established a solid presence since about the middle of the twelfth century.

In the 14th century, the future of music is decisively changed by the transition from the minnesong to the meistersong. The latter has originated in Mainz, and from here spread to the principal cities of Germany.

By this transition the study of Medieval music passed to the city burghers. Guilds were established, and the laws which governed them imposed a certain restraint upon the free development of the musical art.