Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts

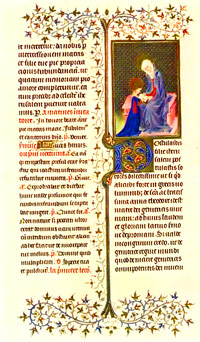

The Medieval illuminated manuscripts aimed at the gratification of those who loved books, and the main purpose of the art of illumination was to make books beautiful. Technically, books containing pictures or ornamental letters in sweet colours and elegant drawing do not constitute illuminations, though they did contribute towards the advancement of art.

Illuminated Manuscripts

Celtic Letter

The Book of Durrow, 7th century

In the 12th century, an illuminator was the person who practised the art of book decoration, using bright colours and burnished gold. Hence the definition of the Medieval illuminated manuscript: a perfect illumination must contain both colours and metals.

At the period when illuminating was at its best, the miniature (a term designating a little picture) was just beginning to appear as a noticeable feature. Gold was as freely applied to it as to the penmanship or the ornament.

The term "miniature" derives from the Latin word minium (red paint), two pigments being known by this name: one is the sulphide of mercury, known also as "vermilion," the other a lead oxide, called "red lead," this one being the minium of the illuminators, though both were used in manuscript work. The red paint was used to mark the initial letters or sections of the manuscript. Due to French writers confusing the term minium with their own language word "mignon" (small and pretty), we got the "miniature."

Illuminated Letter

The Book of Durrow

Illuminated manuscripts were written on vellum, a material made from calfskin. Prepared skins of oxen or pigs were chiefly used for bindings, and occasionally for leaves of books subjected to rough usage, like accounting books. Before the 10th century the vellum was highly polished and very white and fine. After a period when the vellum became thick and rough, towards the Renaissance period it gradually regained its better qualities.

Vellum and parchment are quite different, and is not a mere difference of thickness. Generally vellum is stouter than parchment, however some types of vellum may be thinner than certain parchment. They are made from different kinds of skin, as parchment was traditionally made of sheepskins. Parchment was used for manuscripts, as well as for school, college treatises, or legal documents.

The fabrication of both parchment and vellum in the Middle Ages was a very important process, and certain monasteries achieved a special reputation for the excellence of their manufacture, as was the case with the Cluny Abbey.

The early Medieval Irish manuscripts, "The Book of Durrow," and "The Book of Kells," together with those produced in the same style in England, are unrivalled in delicacy and minuteness, results of a faultless execution. The warlike Normans, did not do too much to restore the taste for learning. English progress in illumination was thus slowed, while in France and Germany new styles appeared, corresponding with the period of Romanesque architecture.

After the marriage of Henry II Plantagenet with Eleanor of Aquitaine, French influence became predominant in English illumination. For about one hundred years, the styles in England and France were almost identical. Gradually, the Romanesque features disappeared, and by the middle of the 13th century, the Medieval illumination attained the perfection of Gothic architecture.

In the execution of Medieval illuminated manuscripts of the 12th and 13th centuries, the pen played a more important part than the brush. While the pen was almost exclusively employed in outlining both foliage and figures, the use of the brush was generally limited to filling up and shadowing the forms defined by the pen.

Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

April - Limbourg Brothers, 1412-1416

The patterns of the 13th century illumination were borrowed from the stained-glass art. The black outlines played the role of the lead lines which in stained-glass works kept the forms and colours distinct. The firm, dark outlining was retained in England later than in France, and the influence of stained-glass techniques in the art of illumination persisted as late as the 15th century.

The initial letters, which in Romanesque illumination had expanded into very large proportions, were now diminished. In compensation, the floriated terminations appeared. They were carried down the side of the page, and even extended across both the top and bottom.

Under the reigns of the three first Edwards in England, the tail of the initial letter, running down the side of the page, gradually widened, until it grew into a band of ornament, occasionally paneled, and with small subjects introduced into the panels. In such cases, the initial letter occupying the angle formed by the side and top ornaments of the page, became subsidiary to the bracket-shaped bordering, which, in earlier examples, had been subsidiary to the initial letter.

In the 14th century, illumination was very popular among the high rank families in England. Numerous coats of arms were emblazoned in many of the most remarkable English manuscripts.

During the 14th and first half of the 15th centuries, the application of raised and highly-burnished gold became a leading feature of the Medieval illuminated manuscripts in both England and France, reaching artistic excellence.

Breviary of John, Duke of Burgundy

French, 1404-1419

In the last half of the 14th century and the beginning of the 15th, under the patronage of Jean, Duke of Berry, the Medieval French art of illumination attained perfection.

The “Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry”, by Limbourg brothers, and some works closer to the Renaissance, as the "Hours of Anne of Brittany," executed about the year 1500, are magnificent examples. In the manuscripts of the period of the Duke of Berry, the lace-like foliation known as the Ivy pattern was perfect. This pattern had an extraordinary popularity in France, England, and the Netherlands. Under the influence of Van Eycks and that of the Italian school, the diapered background was replaced by an architectural, and then a landscape one.

Medieval Spanish manuscripts were heavily influenced by the French models, and subsequently, Netherlandish and Italian styles, their techniques being better exemplified by any of the works of these schools.

The French illuminated manuscripts reached perfection in elegance of ornaments, the intricate interlacements attained the highest level in Irish illuminations, energy of expression and noble tones of colors are characteristic to English manuscripts, while the Italians introduced the high qualities of their painting art in the illumination of Medieval manuscripts.